Exploring ‘Morphic Resonance Learning’ in Wildlife Rehabilitation

The ultimate goal of wildlife rehabilitation is to return a healthy and well adjusted animal back into the wild. Behind the scenes lies an intricate dance of science and intuition, where caregivers strive not just to heal the body, but also to nurture and protect the spirit and instincts of the animals in their care, and the heart of this approach lies a profound and useful concept: morphic resonance learning.

Understanding Morphic Resonance: A Bridge Between Science and Mystery

Morphic resonance is a term coined by biologist Rupert Sheldrake, which delves deeply into the interconnectedness of all living beings and suggests that patterns of behaviour and learning are not just encoded in an individual’s genes or brain but are instead a product of a collective memory inherent in the species as a whole. In other words, organisms draw upon a shared pool of knowledge that transcends the limits of individual experience.

One compelling example of morphic resonance learning in action is observed in the migration patterns of birds. Through generations, bird species like the Arctic tern develop intricate migration routes spanning thousands of miles. Despite the absence of direct guidance from older generations, young terns instinctively embark on the same migratory journey each year. This phenomenon suggests an inherent knowledge passed down through the collective consciousness of the species, guiding individuals to their seasonal destinations.

In her book “The Chimpanzees of Gombe: Patterns of Behavior,” Dr Jane Goodall documents instances where chimpanzees in separate groups exhibit similar behaviours despite their geographic isolation. For instance, she describes how different troops of chimpanzees develop unique tool-using techniques to access food sources. Despite lacking direct contact with each other, these chimpanzee groups often demonstrate remarkably similar tool-making and tool-using behaviours.

The implications of morphic resonance in wildlife rehabilitation, offers a fascinating lens through which to examine the intricate needs and abilities of the species in our care. In this context, morphic resonance learning can become a guiding principle, shaping the interactions between caregivers and their animal charges.

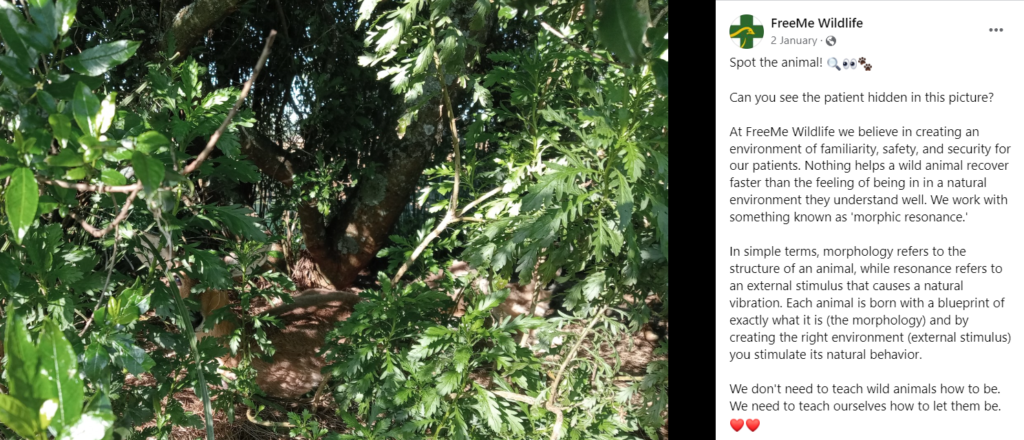

The post below from FreeMe Wildlife in KZN is a perfect example of using morphic resonance learning in wildlife rehabilitation

Case Studies in Morphic Resonance Learning

Take for example, the case of a young owl orphaned after a storm. Some traditional rehabilitation methods prescribe a strict regimen of feeding and exercise in a sterile environment, and while the bird’s wounds were healing, he was not thriving. Sensing a deeper need, the caregivers turned to the principles of morphic resonance and immersed the owl in an environment reminiscent of its natural habitat. With patience and a subtle shift in approach, the bird regained his vitality and began to exhibit a range of natural behaviours, which is exactly what you want to see as a wildlife rehabilitator because it means your patient is well on their way to not needing you anymore.

In a domestic context it is just as crucial to understand the natural and instinctive behaviours of specific species. You can use this knowledge to create a safe and nurturing environment for a rescued rabbit or even a dog, pig, sheep or snake.

Application of Morphic Resonance Learning in animal husbandry and dealing with wildlife in distress

Minimising human interaction and stimuli when dealing with wildlife

Minimising human contact and stimuli such as sounds and smells is paramount to keeping stress levels down, and ensuring the successful reintegration of animals back into the wild. Human interaction, while well-intentioned, can inadvertently imprint animals with behaviours or dependencies that hinder their ability to thrive in the wild. Minimising human contact also mitigates the potential for stress, anxiety, and behavioural abnormalities that can arise from prolonged captivity or exposure to unfamiliar stimuli.

Understanding the Species’ Natural Behaviour and Creating an Enriching Environment

It is always crucial to thoroughly understand the natural behaviour, habitat, and requirements of the species in your care. Do they climb or burrow? Are they nocturnal or diurnal? Do they stash their food or hunt on the wing? Are they solitary or do they live in groups? What are their social structures? This knowledge forms the foundation for creating an environment conducive to morphic resonance learning, which you can apply to your animal husbandry.

Observation and Recordkeeping:

Spend time observing the animal’s behaviour and interactions within the enclosure. Encourage natural behaviours such as foraging, grooming, and socialising by providing appropriate stimuli and opportunities. Keep records of any changes you see and take note of what works and what needs improving.

Facilitating Social Learning:

If possible, house relevant animals with members of their own species, or individuals of similar species. Social interaction provides opportunities for observational learning and the transmission of natural behaviours. Even if direct interaction is not possible, the presence of other animals can still influence learning through observation. Even playing recordings of the species can alleviate stress, which in turn promotes healing.

Encourage Problem-Solving and Exploration:

Introduce environmental challenges and ‘puzzles’ that encourage the animal to engage in problem-solving and exploration. This could include hiding food items to encourage foraging, introducing objects they would come across in their natural habitat for manipulation, or creating opportunities for the animal to navigate obstacles.

Conclusion:

By incorporating the principles of morphic resonance learning into wildlife rehabilitation efforts, caregivers can enhance the physical and behavioural well-being of rehabilitated animals and increase their chances of successful reintegration into their natural habitats.

References:

Sheldrake, Rupert. “A New Science of Life: The Hypothesis of Formative Causation.” J.P. Tarcher, 1981.

Goodall, Jane. “The Chimpanzees of Gombe: Patterns of Behavior.” Belknap Press, 1986.

![Give A HOOT! [Watch]](https://gracevalleyhaven.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Spotty.jpg)

![Going Batty [Watch]](https://gracevalleyhaven.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/trevor-gerzen-jC8uzTM8PlM-unsplash-1.jpg)

One response to “Morphic Resonance Learning”

[…] Read more about Morphic Resonance Learning in the context of wildlife rehabilitation… […]